Inauthentic Prestige Blade

In the style of the Yakoma (although originally labeled Azande-Idio), D.R. Congo / C.A. Republic

Iron, ivory, copper

Manufactured by Tilman Hebeisen (Austria) in 2004

Provenance dates back to 2006

This knife was manufactured by the Austrian blacksmith Tilman Hebeisen in 2004, commissioned by Peter Hasenkopf. Its history is almost unbelievable.

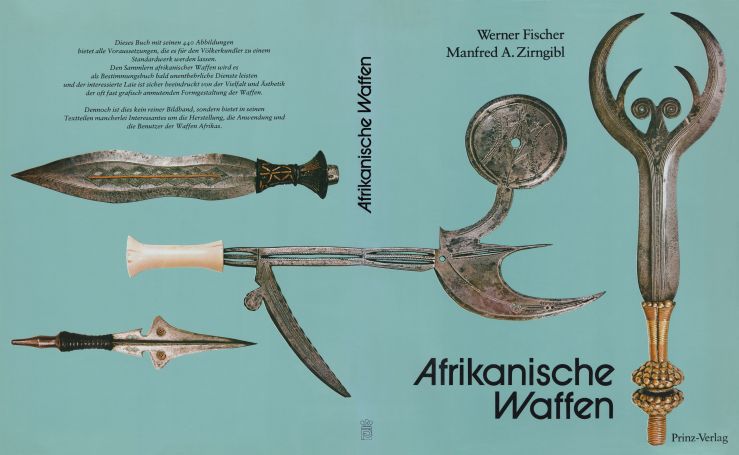

In 1978, Werner Fischer and the late Manfred Zirngibl published Afrikanische Waffen (African Weapons), the first truly comprehensive book dedicated strictly to African knives. The cover features four fine blades, prominent among them a spectacular ivory-handled prestige knife with radical projections and elaborate incisions in a form that no one had previously seen.

Fischer and Zirngibl attributed the blade to the Azande-Idio, but the blade type is most commonly attributed to the Yakoma or Zande (it will be referred to as Yakoma below). Though its provenance contains some suspicious information, the remarkable form and beauty of this rare masterpiece virtually guaranteed that it would appeal to collectors, dealers, and auction houses, and indeed this proved to be true. At the time it was published, it was the only example known. It was in the collection of one of the authors, Manfred Zirngibl.

Over the years, several other weapons of this rare type have come to light and have fetched significant prices on the art market. However, viewed from a perspective of expertise, these seem to have more in common with each other than with the one that appears in Fischer and Zirngibl. A close examination of this example reveals troubling details.

A significant inconsistency can be found in the way in which the iron was worked. A knife produced at the forge by a traditional blacksmith in Africa will show signs of being drawn out and wrought into its final shape. Certain elements should be visible, such as slag streams resulting from this manipulation of the iron and overlaps that show where separate pieces of iron were hammered onto other pieces to join them. The iron on the Rider Yakoma shows no sign of such traditional forging and was likely cut from a solid sheet.

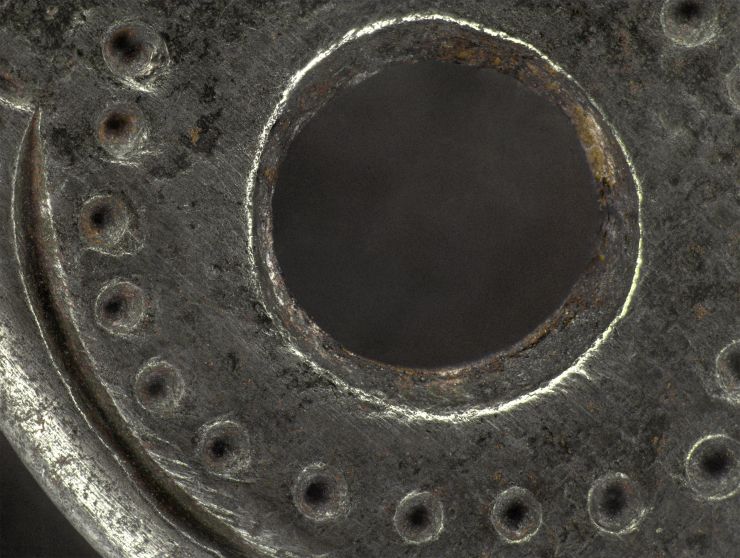

The incised decorations on this Yakoma are also problematic. Although many of the patterns on the blade are inconsistent with traditional Yakoma designs, the manner in which they were executed is patently incorrect. The markings on authentic Yakoma blades, as well as on other blades from the region, were achieved by a process of punching and/or hammering, often carried out while the iron was still hot. Here, however, the incisions are burned in.

[Correction: In 2018, I used the term "burned in" to describe the incisions and dragged lines on this iron blade to explain their entirely non-African execution. There was a consensus that these incisions were extremely incorrect, and could have been applied with a modern technique, such as burning in. However, I was informed by other colleagues that the notion of "burning in" such fine details wasn't feasible. In speaking directly with Hebeisen, I learned that the tool he used to execute these incisions was indeed a non-African tool, seen here, but certainly not one capable of "burning in."]

While this isn’t immediately visible to the naked eye, it is blatant under magnification. Photographed at 20x magnification, both the extremely consistent circular cone incisions, which indicate the shape of the tool that was used, and the crisscrossed lines along the stem show undeniable evidence of the same inappropriate technique.

Stylistically, the incised lizards are far too naturalistic. While the lizard is a recurring theme, no traditional knife from Africa depicts one with such realism, and especially not with the muscular legs seen here. Abstracting the form of a lizard is something an African blacksmith would take pride in doing, as embodying the creature’s avatar, or symbolic spirit, would be much more important than producing a lifelike representation.

An additional small but telling oversight appears in the copper rivet which is—incorrectly—bulging and rounded on both sides. With authentic African metalwork from this region, such rivets are flat on one side and rounded and attractive on the other.

This technical analysis seems damning to this Yakoma and, by extension, the other examples that have more in common with it than with the example in Fischer and Zirngibl. Our reasons for believing these Yakoma blades are inauthentic go far beyond the analysis of a single example.

In 2009, Alexander Kubetz and Manfred Zirngibl (co-author of the above-mentioned Afrikanische Waffen) published Panga Na Visu, an encyclopedic book on African weapons that is packed with photographs. While some consider it an excellent reference book, others find it to be something of a curiosity because it presents numerous knives that seem suspect or obviously inauthentic alongside knives that are old, rare, and widely accepted as authentic.

In 2014, a provocative comment appeared on the website afropapa.de in a discussion thread about Panga Na Visu. An obviously disgruntled reader wrote, “Aber Hallo, Ein schönes Buch???? Ja??? alles echt??? Ja?? Ich biege mich vor lachen ‘Schmiedekunst’!!” which roughly translates as “Hold on there, nice book? Yes? All are real? Sure? I'm bent over with laughter, ‘blacksmithing’!!” The emphatic disdain piqued the interest of long-time African weapons collector and expert Wolf-Dieter Miersch, who had recently become aware of some suspicious transactions between Zirngibl and a German museum, and was interested in pursuing leads about his other dealings.

Miersch contacted the author of the online comment, one Tilman Hebeisen, and after a 90-minute phone call, he realized that Hebeisen was the key to unlocking the door to Zirngibl’s incredibly strange world of secrets. A blacksmith by trade, Hebeisen declared that Zirngibl, who had long collected and dealt in African weapons but whose academic background lay in business administration, hired him in 1976 to manufacture replicas of African knives in Austria, and that he had been doing this work for decades.

On November 18, 2015, Miersch traveled to meet the 83-year-old Hebeisen in the town of Wernstein on the Austria/Germany border, only eight km away from Zirngibl’s hometown of Passau. A series of conversations with Hebeisen conducted by Miersch furnished the basis of much of the material presented herein. The interviews began in November 2015 and continue to this day. In 2016, Ingo Barlovic, a member of the editorial staff of the German magazine Kunst & Kontext, also paid a visit to Hebeisen in Wernstein. Barlovic published an article about his interviews with Hebeisen in the July 2017 issue of Kunst & Kontext.

Hebeisen related that he completed his apprenticeship as a blacksmith in Munich and fabricated artistic fences and gates as well as crosses for cemeteries. He described work experience during the 1960s that involved making European objects “look old fashioned.” After moving to Wernstein in 1976, he was contacted by Zirngibl, who was to present him with a great deal of work. Zirngibl proposed a succession of projects, starting with repairs to antique African knives, then moving on to the production of seemingly vintage African weapons that he claimed were for clients who couldn’t afford authentic examples. For Hebeisen, Zirngibl’s requests were a pleasure to fulfill, as they represented an opportunity to be creative with his craft.

Following the publication of Afrikanische Waffen in 1978, Zirngibl commissioned Hebeisen to manufacture two versions of the spectacular ivory-handled blade that was pictured on the cover. While based on the singular original knife, each one intentionally displayed its own artistic idiosyncrasies. Over the course of the next twenty-five years, Hebeisen would manufacture roughly a dozen more.

According to Hebeisen, the ivory handles were supplied by Zirngibl, who had either taken them from old knives, or ordered them from an Austrian carver he’d described as ‘fantastic.’ Indeed, the handles are expertly carved, with balanced, graceful curves, and their surfaces wear a convincing patina like that from years of handling. The ivory itself exhibits believable marks of crazing (an attribute that typically develops with the passing of time), and none of the telltale signs of artificially induced crazing, like discoloration. Because Hebeisen had the ivory handles before he manufactured the blades, he was able to manipulate the iron so that it would protrude through the bottom of the ivory handle. This subtle detail is present on many authentic African knife types, lending credence to Hebeisen’s blades.

Though Hebeisen was a sound blacksmith, his techniques were not African, as the analysis of this Yakoma revealed. But in case any doubt remains that these blades were not manufactured by the Yakoma, Hebeisen produced several significant photographs during his interviews with Miersch. One depicts this very blade and others depict the two Yakomas that Hebeisen would later discover on the market that led to his distressing revelation that he was not in fact creating artistic reproductions, but rather forgeries. Other photographs show partially completed blades in conjunction with a sketch in one case and a full-size photocopy of the original Yakoma knife. All of these photographs were taken by Hebeisen in his home in Austria.

By placing the radically extravagant and authentic Yakoma blade on the cover of his 1978 book Afrikanische Waffen, Zirngibl guaranteed its significance as a rare object and reinforced its considerable value. Since there was only one original, it was the perfect object for him to have copied, guaranteeing that he would be both the expert on the type and the only dealer who had examples for sale.

After producing both replica and fantasy knives for Zirngibl and other dealers for decades, Hebeisen states that he finally became aware of the consequences of his work. While he initially thought he was making creative replicas for collectors who couldn’t afford authentic blades, he began to suspect that he was actually participating in a scheme to deceive. The first clue came in 1995, when he saw one of his blades in a gallery in Munich and requested the price. The response came in a letter, quoting 65,000 Deutsche Marks, roughly $45,000. Although alarming, it was, for the time being, an isolated incident, and Hebeisen continued to produce.

In 2008, Hebeisen found one of his Yakoma blades in a Paris auction, estimated at €11,000–13,000, and in 2013, he saw another of his Yakoma knives sold by a prominent auction house for $17,500 (here). He now knew that he had been duped, finally understanding that the creative projects that Zirngibl and others had brought him in fact had made him a key part of a lucrative and dishonest enterprise. He posted his aggrieved comment on afropapa.de, and thus began the unveiling of the provenance of his knives.

To his credit, while he had participated in questionable activities for decades, Hebeisen has been willing to share his story and expose the truth, supported by the photos he had taken of his replica knives in their various stages of production, including his makaraka blades, of which he made at least 15, identifiable by their flamboyant handles.

Scholarly focus on African blacksmithing techniques involving meticulous comparisons of Hebeisen’s knives with traditional examples undoubtedly would have resulted in the exposure of these forgeries sooner or later, but the fact that he has fully acknowledged his complicity has moved the conversation to the fore. There are others involved in this deceptive trade who have declined to follow his lead or who have taken their secrets to the grave.

A clear indication of the success that Hebeisen’s knives have achieved is that they are currently being reproduced in Africa, which demonstrates the African blacksmith’s proactive response to the demands of the European market.

References:

Barlovic, Ingo. “Geschmiedete afrikanische Kurzwaffen made in Österreich?” Kunst & Kontext, July 2017.

Fatal Beauty: Traditional Weapons from Central Africa, ed. Marc Leo Felix. Taiwan: Suhai Design and Production, 2009.

Fischer, Werner, and Manfred A. Zirngibl. Afrikanische Waffen. Passau: Prinz-Verlag GmbH, 1978.

Lefebvre, Luc. NGBANDI YAKOMA: Armes Tradtionnelles. 2017.

Spring, Christopher. African Arms and Armor. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993.

Westerdijk, Peter. The African Throwing Knife: A Style Analysis. Utrecht: OMI, 1988.

Zirngibl, Manfred A. and Alexander Kubetz. Panga Na Visu. Riedlhütte: Hepelo Publishing, 2009.

Zirngibl, Manfred A. Seltene Afrikanische Kurzwaffen: Rare African Short Weapons. Grafenau: Morsak Publishing, 1983.

17.5 in :: 45 cm

InventoryID #13-1082

Not For Sale