Ceremonial / Status Axe

In the style of the Lunda / Chokwe, D.R. Congo

Steel, copper, wood

1990s

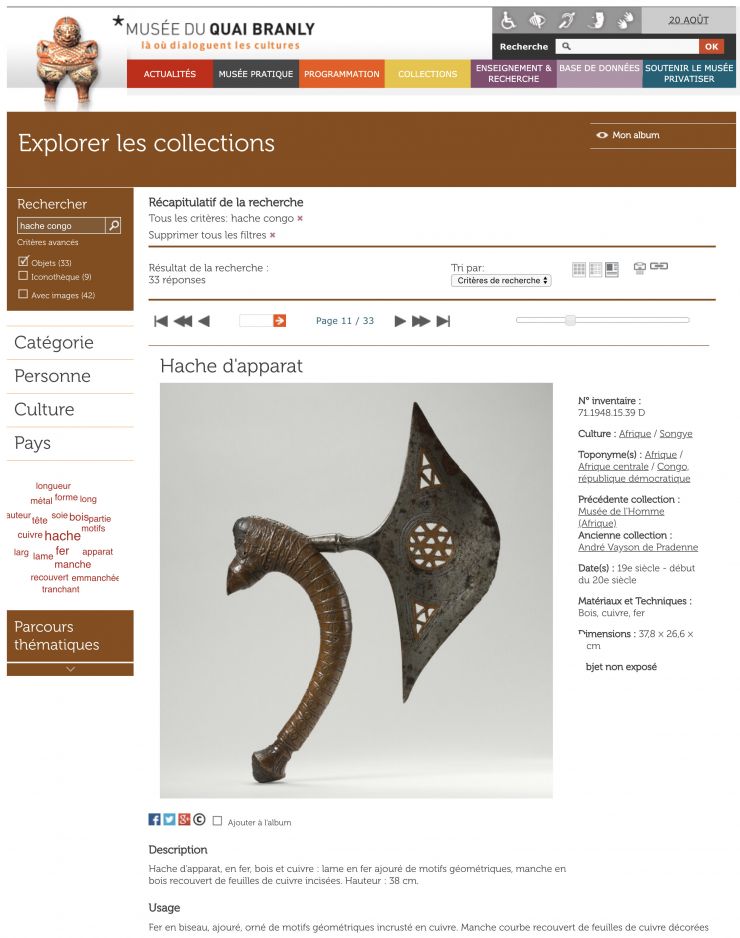

There is an old example of this axe type in the Musée du Quai Branly collection. Exhibited in the “Striking Iron” show, it was acquired in 1948. In the 1990s, a handful of other examples appeared on the market without documented provenance, including this piece.

What we see here is a carved wood handle with a curve that emphasizes tension, wrapped in copper tape that has been carefully hand-stapled to the wood and embossed (just like the 1948 piece). This is top quality workmanship and difficult to question. The problematic areas aren’t visible until we look away from the handle.

First and foremost, the iron has been acid-etched to simulate age and pitting. While there are many techniques for chemical modification, this piece was likely etched with nitric acid. The corrosion that nitric acid creates is different from natural corrosion in that it creates more vertical cuts in the surface of the iron. The sharp delineation between the clean and corroded areas is clearly incorrect and inconsistent with the natural process. Even more telling, the axe was only etched on one side. While many blades exhibit different degrees of exposure on different sides (for example, from being left with one side up and one side down for years), the Jekyll and Hyde nature of the two sides of this axe is extremely unnatural.

The large copper inserts certainly offer valuable insights as well. The only way to accomplish this visually stunning combination of metals was to manufacture them separately, because of the different melting and working temperatures of each metal. First the iron would be forged with large areas of negative space, and then cooled and hardened. Then, copper inserts would be crafted to almost exactly the size of the holes in the iron, being incised and pierced and completed as stand-alone works of art. Then the copper inserts would be hammered into the steel, which would make them expand slightly and thus keep them in place inside the steel holes.

The copper inserts seen on this axe are clumsy and careless, which are characteristics we don’t see on the 1948 blade. Additionally, the interior walls of the negative spaces (inside the cut-outs) are clean and vertical. What I would expect to see on an authentic piece of large copper like this is a number of chisel marks on the interior walls, but these large cuts seems to be made instead with Western tools. The minimal amount of hammering used to insert the copper is also indicative of a non-traditional technique. When the copper disc is hammered to insert it into the iron void, the copper is expanded and thus slightly warped. This piece of copper is barely changed from its original state.

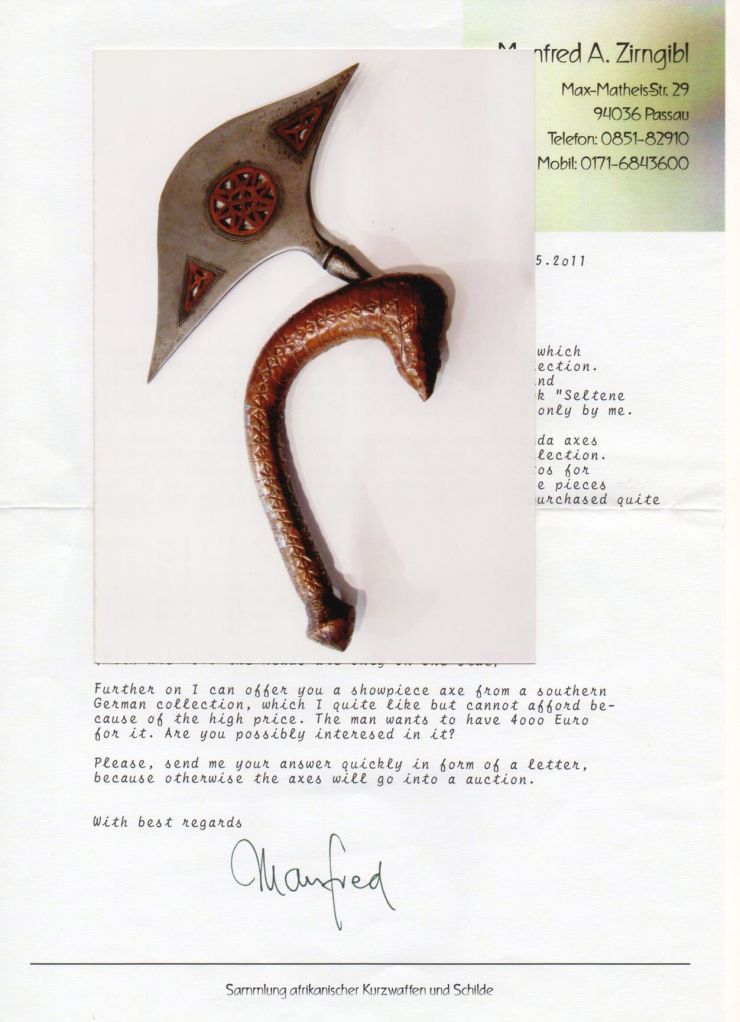

Importantly, Manfred Zirngibl, who is now famous for inventing and commissioning inauthentic African knives, offered this very axe for sale in 2011:

16.5 in :: 42 cm

InventoryID #13-1404

Not For Sale