Copper Double-Eye Musele

In the style of the Kota, Gabon

Solid copper

Early 1980s

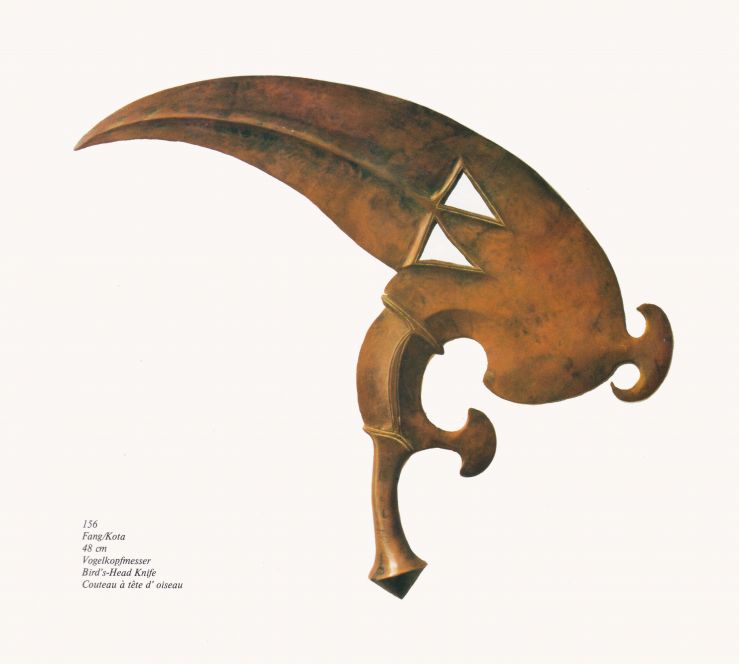

Tilman Hebeisen was an Austrian blacksmith who devoted most of his time to fabricating artistic fences and gates as well as crosses for cemeteries after completing his apprenticiship in Munich in the 1960s. After moving to Wernstein in 1976, he was contacted by Manfred Zirngibl, who was to present him with a great deal of work. Zirngibl proposed a succession of projects, starting with repairs to antique African knives, then moving on to the production of seemingly vintage African weapons that he claimed were for clients who couldn’t afford authentic examples. Finally, Zirngibl delivered eight 360 x 160 x 10 mm copper sheets to Hebeisen and asked him to invent a new knife based on the iron Kota double-eye musele, pictured below.

Collection Allan Ridel / Memoire Africaine

In 1983, Zirngibl published Seltene Afrikanische Kurzwaffen (Rare African Short Weapons), which featured a masterpiece knife that had never been seen before: an oversized solid-copper Kota musele blade.

This exceedingly rare and unusually obscure type quickly became one of the most highly sought after African knives, and to this day, they sell for prices consistently higher than most other African knives.

Over the course of three years in the late 1970s, Hebeisen made five copper musele knives, each imbued with its own personality. These original five copper knives were often referred to as the famous five copper knives of Sir George Fullham.

After the publication of Seltene Afrikanische Kurzwaffen, Zirngibl encountered a client who wanted to purchase the copper blade published in the book (Hebeisen’s first Kota), but since Zirngibl had decided to keep it, he commissioned Hebeisen to manufacture a similar knife. According to Hebeisen, he disliked the task of copying his previous work, as it limited his creativity, and was a greater challenge than inventing a new piece. But he obliged, and the result was a sixth example (the piece presented here), which differs from the published example only in small details of proportion.

Hebeisen did not create another copper Kota until 2003, long after his relationship with Zirngibl had ended in 1992, when a different art dealer commissioned one. That piece, his seventh, eventually found its way into the pages of the original (orange) catalog of Fatal Beauty: Traditional Weapons from Central Africa, the comprehensive 2009 Taiwan exhibition. Hebeisen provided a photograph of this very knife propped up on a rock in his garden, taken in 2003.

In keeping with his practice of creating false histories for his knives, Zirngibl had provided two pieces of evidence to a private collector who purchased one of the famous five copper knives. The first piece of evidence is a picture of two pages purportedly from the L.A. Smith book, which told the wild tale of these five knives being rewarded by a chief for curing an eye infection. Ingo Barlovic determined this document to be a composite of invented material and snippets from a 1913 book about a Ugandan journey (Barlovic published a photo of this doctored two-page spread in his article in Kunst & Kontext).

The second piece of evidence Zirngibl provided was a Polaroid photograph of a photograph that is shrouded in mystery. The owner of the photograph will not allow it to be seen. A witness present on the day the photograph was staged will not allow her name to be revealed. However, both Barlovic and Wolf-Deiter Miersch have seen the photograph, which shows four of the five original copper Kotas hanging on a wall alongside an iron example.

Hebeisen made only seven of these blades, which are large and artistically distinctive. Incredibly, when Miersch visited Hebeisen in 2015, he still had the eighth and final copper plate from the original batch that Zirngibl had provided him nearly forty years earlier.

However, his seven blades have been copied repeatedly over the years, forming a genre unto itself.

In fact, one copy of Hebeisen’s inventions is on display in the Schweiklberg Black Africa Museum in Southeastern Germany, and another copy by the same hand appeared at a prominent auction house in 2011.

The fact is, no solid-copper Kota blade exists in any early collection—the blade type simply did not exist before Zirngibl invented it. Furthermore, there are no other knives from Africa constructed of a single solid piece of metal—blade and handle are always two distinct pieces, even when both elements are composed of metal.

After producing both replica and fantasy knives for Zirngibl and other dealers for decades, Hebeisen states that he finally became aware of the consequences of his work. While he initially thought he was making creative replicas for collectors who couldn’t afford authentic blades, he began to suspect that he was actually participating in a scheme to deceive. Hebeisen found a number of his pieces for sale for significant sums across Europe, and finally understood that he had been duped.

To his credit, while he had participated in questionable activities for decades, Hebeisen has been willing to share his story and expose the truth, supported by the photos he had taken of his replica knives in their various stages of production. Scholarly focus on African blacksmithing techniques involving meticulous comparisons of Hebeisen’s knives with traditional examples undoubtedly would have resulted in the exposure of these forgeries sooner or later, but the fact that he has fully acknowledged his complicity has moved the conversation to the fore. There are others involved in this deceptive trade who have declined to follow his lead or who have taken their secrets to the grave.

A clear indication of the success that Hebeisen’s knives have achieved is that they are currently being reproduced in Africa, which demonstrates the African blacksmith’s proactive response to the demands of the European market.

This story could not be written without the efforts of Wolf-Deiter Miersch. He is pictured (left), in the home of a collector who purchased many of Hebeisen's knives.

References:

Barlovic, Ingo. “Geschmiedete afrikanische Kurzwaffen made in Österreich?” Kunst & Kontext, July 2017.

Fatal Beauty: Traditional Weapons from Central Africa, ed. Marc Leo Felix. Taiwan: Suhai Design and Production, 2009.

Lefebvre, Luc. NGBANDI YAKOMA: Armes Tradtionnelles. 2017.

Spring, Christopher. African Arms and Armor. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993.

Westerdijk, Peter. The African Throwing Knife: A Style Analysis. Utrecht: OMI, 1988.

Zirngibl, Manfred A. and Alexander Kubetz. Panga Na Visu. Riedlhütte: Hepelo Publishing, 2009.

Zirngibl, Manfred A. Seltene Afrikanische Kurzwaffen: Rare African Short Weapons. Grafenau: Morsak Publishing, 1983.

17 in :: 43 cm

InventoryID #13-1248

Not For Sale